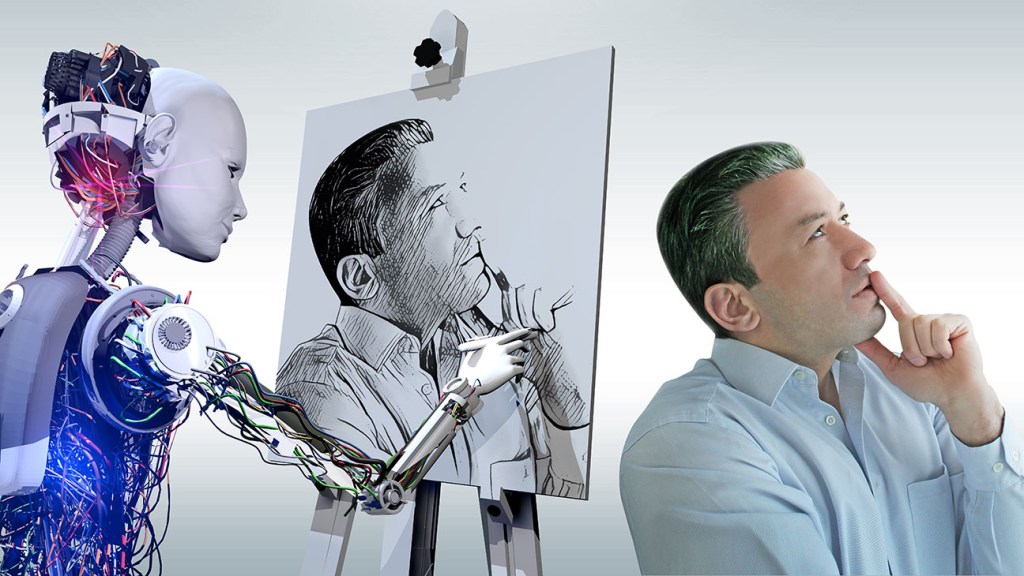

More than 100 days into the writers strike, fears have kept mounting over the possibility of studios deploying generative artificial intelligence to completely pen scripts. But intellectual property law has long said that copyrights are only granted to works created by humans, and that doesn’t look like it’s changing anytime soon.

A federal judge on Friday upheld a finding from the U.S. Copyright Office that a piece of art created by AI is not open to protection. The ruling was delivered in an order turning down Stephen Thaler’s bid challenging the government’s position refusing to register works made by AI. Copyright law has “never stretched so far” to “protect works generated by new forms of technology operating absent any guiding human hand,” U.S. District Judge Beryl Howell found.

The opinion stressed, “Human authorship is a bedrock requirement.”

The push for protection of works created by AI has been spearheaded by Thaler, chief executive of neural network firm Imagination Engines. In 2018, he listed an AI system, the Creativity Machine, as the sole creator of an artwork called A Recent Entrance to Paradise, which was described as “autonomously created by a computer algorithm running on a machine.” The Copyright Office denied the application on the grounds that “the nexus between the human mind and creative expression” is a crucial element of protection.

Thaler, who listed himself as the owner of the copyright under the work-for-hire doctrine, sued in a lawsuit contesting the denial and the office’s human authorship requirement. He argued that AI should be acknowledged “as an author where it otherwise meets authorship criteria,” with any ownership vesting in the machine’s owner. His complaint argued that the office’s refusal was “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion and not in accordance with the law” in violation of the Administrative Procedure Act, which provides for judicial review of agency actions. The question presented in the suit was whether a work generated solely by a computer falls under the protection of copyright law.

“In the absence of any human involvement in the creation of the work, the clear and straightforward answer is the one given by the Register: No,” Howell wrote.

U.S. copyright law, she underscored, “protects only works of human creation” and is “designed to adapt with the times.” There’s been a consistent understanding that human creativity is “at the core of copyrightability, even as that human creativity is channeled through new tools or into new media,” the ruling stated.

While cameras generated a mechanical reproduction of a scene, she explained that it does so only after a human develops a “mental conception” of the photo, which is a product of decisions like where the subject stands, arrangements and lighting, among other choices.

“Human involvement in, and ultimate creative control over, the work at issue was key to the conclusion that the new type of work fell within the bounds of copyright,” Howell wrote.

Various courts have reached the same conclusion. In one of the leading cases on copyright authorship, Burrow-Giles Lithographic Company v. Sarony, the Supreme Court held that there was “no doubt” that protection can be extended to photographs as long as “they are representative of original intellectual conceptions of the author.” The justices exclusively referred to such authors as human, describing them as a class of “persons” and a copyright as the “right of a man to the production of his own genius or intellect.”

In another case, the a federal appeals court said that a photo captured by a monkey can’t be granted a copyright since animals don’t qualify for protection, though the suit was decided on other grounds. Howell cited the ruling in her decision. “Plaintiff can point to no case in which a court has recognized copyright in a work originating with a non-human,” the order, which granted summary judgment in favor of the copyright office, stated.

The judge also explored the purpose of copyright law, which she said is to encourage “human individuals to engage in” creation. Copyrights and patents, she said, were conceived as “forms of property that the government was established to protect, and it was understood that recognizing exclusive rights in that property would further the public good by incentivizing individuals to create and invent.” The ruling continued, “The act of human creation—and how to best encourage human individuals to engage in that creation, and thereby promote science and the useful arts—was thus central to American copyright from its very inception.” Copyright law wasn’t designed to reach non-human actors, Howell said.

The order was delivered as courts weigh the legality of AI companies training their systems on copyrighted works. The suits, filed by artists and artists in California federal court, allege copyright infringement and could result in the firms having to destroy their large language models.

In March, the copyright office affirmed that most works generated by AI aren’t copyrightable but clarified that AI-assisted materials qualify for protection in certain instances. An application for a work created with the help of AI can support a copyright claim if a human “selected or arranged” it in a “sufficiently creative way that the resulting work constitutes an original work of authorship,” it said.

Weirdly enough, it might.

I mean, sure, an orange room doesn’t qualify for copyright.

But if you instruct helpers to help you make a copyrightable work to your specifications (e.g. architects instructing workers to build the building), then you own the copyright.

It all comes down to who had what part of the creative process.

For example, if I create a digital artwork and I use an AI tool to increase the resolution, I totally still own the artwork.

I am also pretty sure I retain the copyright if I let an AI fix my spelling in a story I wrote.

But if my input is negligable (“Write me a short story.”), I definitely don’t have the copyright.

Copyright law is complicated and there’s never a clear general answer.

“For example, if I create a digital artwork and I use an AI tool to increase the resolution, I totally still own the artwork.”

There are tools that allow you to convert a stick figure drawing plus a prompt into whatever you want. I can draw a stick figure holding a circle and prompt it as a bunny holding an apple and I could get the desired output. Of course thats more than increasing resolution but where do we draw the line.

we let the AI draw it for us

That’s what I said, yeah.

The line is probably drawn where it is drawn when using any other tool: For your contribution to be copyright-worthy it needs to be above the required threshold of originality. Copyright doesn’t distinguish between different tools you use, it just requires you to have put enough creativity into it for it to be a creative work.

AI in this respect is very close to photography.

Just pulling out your phone and snapping a picture of something does not clear the theshold, so you have no copyright over it, no matter how detailled the picture is.

If you set up the scene and put a lot of creative input into preparation and post-processing of the picture, you will clear that threshold and you will have copyright over it.

If this sounds arbitrary and hard to pinpoint whether that threshold (which is not clearly defined anywhere) is cleared, you are totally right. This is a big issue with the copyright system, but it’s also nothing that will be fixed by some people commenting on the internet.

So the question is “Did the human input into the AI tool clear the thresold or not?”

This question is the same, regardless of what tools are used, and it’s a common part of lawsuits concerning copyright. There is no blanket answer and it needs to be checked on a case-by-case basis. That’s how copyright law works.