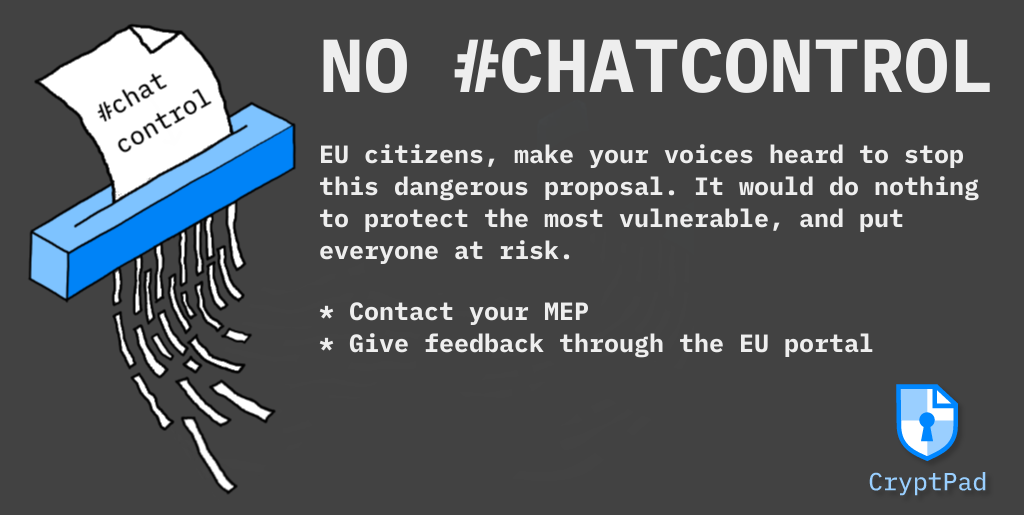

What you can do: https://www.patrick-breyer.de/en/posts/messaging-and-chat-control/#WhatYouCanDo

Contact your MEP: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/meps/en/home

Edit: Article linked is from 2002 (overview of why this legislation is bad), but it is coming up for a vote on the 19th see https://www.patrick-breyer.de/en/council-to-greenlight-chat-control-take-action-now/

What I try to say is that taxes don’t pay for public infrastructure directly. The state creates an expenditure budget, and decides which taxes it’s gonna charge. The fact that many politicians don’t know better and conflate the two, has more to do with ignorance and believing the dogma of neoliberalism, than it has to do with the expenditure of public money and with taxation. Most politicians effectively treat taxes as if they do pay for the public infrastructure, but those concerns suddenly disappear when it comes to rescuing a bank, or to exceeding the military budget, and they remember that states can pay for that stuff without needing to collect that money through taxes in the first place. They even bother to remind us of that when it’s the case. In the 2010 Euro crisis, Spain (I’m Spanish) 60bn € in rescuing a set of Spanish banks. Our then economy minister, Luis de Guindos, kindly reminded everyone that “this isn’t going to cost a single euro to the taxpayer”. So yeah, they only remind us about which stuff “needs” to be paid for taxes when it’s actually important, such as healthcare, education or pensions, but they suddenly forget about that requirement when it comes to increasing military budget extraordinarily after budgets were approved, or to rescue a bank.

Your point about hyperinflation is a good one, and remember that I’m not claiming we should start creating infinite money for everyone. In the EU, for example, we have a theoretical budget deficit limit of 3% for many decades now. If you examine the historical reasons for this limit, it comes from a meeting some decades ago in which some higher-ups of the EU met for some hours to decide on a deficit limit, in the full reagan/thatcher period. They came out of the meeting with the number of the 3% limit, and also with the suggested 60% maximum debt as percentage of GDP. The 3% deficit limit was made up on the spot, literally in 30 minutes by a French economist called Guy Abelle, which he has admitted to later in life. The 60% debt was based on a study that compared the health of economies and their percentage of debt… until the study was found many years later to be faulty, because it had significant errors in the spreadsheets used to calculate that number, and upon correcting that there was no suggested number anymore… Look up “Reinhart and Rogoff mistake” on your favourite search engine. So yeah, those rules are absolutely made up and they don’t obey any experimental or scientific criteria. That’s not to say there shouldn’t be a limit to budget, but the conclusion I want to get across is that deficit isn’t a bad thing since it amounts to increasing the wealth of the public sector, and the limit of deficit should be calculated or even experimented with based on real, empirical data from real economies, and not what some old neoliberal farts decide in a meeting one evening.

I’ll finish with an analysis of a case of hyperinflation, that of Venezuela in the recent years. Venezuela is and has been for the past century an economy based on oil exports. In the year 2014, oil prices were reduced from $130 per barrel, to below half of that. In an economy reliant on oil exports, this meant that Venezuela’s purchase power to the outside world suddenly halved, with a corresponding immense drop in GDP. This is what originally led to a high inflation. Now, the price of goods for citizens is so high that they can barely afford them or not afford them completely. As a state with a central bank, you’re confronted with two choices: you leave things be, and people literally don’t have money to buy their basic needs; or you create money so that people can at least afford them for some time. The response was to create the money to alleviate the harshest consequences. This in turn enables the possibility that people can still buy products that are in shortage, which makes the price even higher, and the cycle restarts. The consequence, as we saw, was hyperinflation. But this hyperinflation wasn’t triggered by money creation, it was triggered by an external event, i.e. the drop to half the price of the country’s biggest export good and biggest sector of the economy. Of course the government could have decided to let the people starve, and there would have been only huge inflation and not hyperinflation, but is that really a solution? The goal is to prevent hyperinflation, or to minimize human suffering? Javier Milei, for example, seems to be currently on the path to “solve” the inflation problem in Argentina… By making the citizens so poor, that they can’t afford to buy the goods and services, so that the businesses can’t rise the prices. Sure, inflation goes down, but not by solving the economic underlying problems, and instead by creating immense amounts of suffering so that “the line can finally go down”.

I appreciate your willingness to listen, all of this seemed crazy to me just a few years ago, but everything makes so much more sens when analysing the economy from the point of view of modern monetary theory, and the predictive capabilities of the theory are so much better, it’s been proven so much during the COVID pandemic and the posterior inflation crisis.

That was an interesting read. Thanks. Do you study economics as part of an education? Or did you just dive in to it out of personal interest?